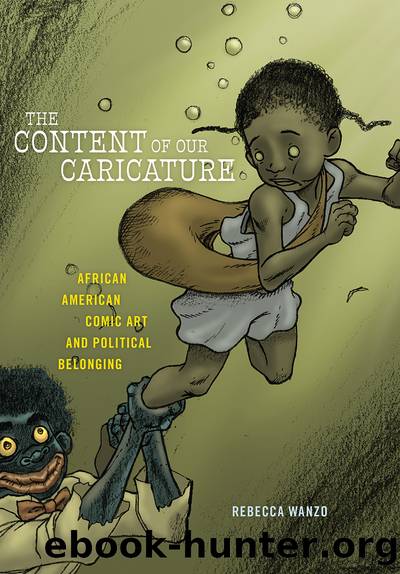

The Content of Our Caricature: African American Comic Art and Political Belonging by Rebecca Wanzo

Author:Rebecca Wanzo [Wanzo, Rebecca]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: LIT004040 Literary Criticism / American / African American, Social Science, African American Studies, Ethnic Studies, American, African American, art

ISBN: 9781479840083

Google: QAS5DwAAQBAJ

Publisher: NYU Press

Published: 2020-04-21T23:51:31.623748+00:00

4

âThe Only Thing Unamerican about Me Is the Treatment I Get!â

Infantile Citizenship and the Situational Grotesque

Just as the African American hero has been antithetical to constructions of white, masculine citizen ideals, black children have been a binary other to romanticized depictions of white children. American visual culture history is filled with this binary, with perhaps Topsy and Eva from Harriet Beecher Stoweâs Uncle Tomâs Cabin being the most explicit examples of a black âpickaninnyâ caricature functioning as opposite to a white angelic girl child. As we saw with the Yellow Kid comic strip, black children are often represented as outside of innocence and something other than children. But some African American cartoonists have turned this caricature of white innocence on its head, marking the universal, idealized childhood as suspect given the material realities facing many children.

Few cartoonists were better at making the white child caricature the Other than Brumsic Brandon Jr. His comic strip Luther (1969â1986) was one of the first nationally syndicated comic strips created by an African American featuring black characters outside of the black press, following Morrie Turnerâs Wee Pals and Ted Shearerâs Quincy. Luther and his friends attended an inner-city school and dealt with poverty, hunger, unseen teacher Ms. Backlash, and a white classmate who stood in for blithe ignorance to black suffering and passive resistance to the black freedom struggle. The unfortunate timelessness of his comic strip is on full display in a 1970 four-panel strip (Figure 4.1) in which Luther and his friend Pee Wee discuss police shootings. Brandonâs strips frequently employ incongruity to produce the joke in the last frame. Here, Pee Wee asks Luther why âso many black people get hurt when . . . the police say they were shooting over their heads?â âWell,â Luther speculates, âa lot of policemen think all black people are BOYS.â In the last frame a close-up of Lutherâs wide, innocent eyes, and round face in his hands delivers the punch line: âSo I guess the cops donât shoot HIGH enough!â

These black children embody a racial melancholia springing from lost objects they cannot quite placeâa mourning and confusion at the violability of black bodies that speaks to the fact their personhood should be cherished and is not. And for readers, grotesquerie lies in the liminality of these cute childrenâs knowledge of monstrous facts. Nineteenth- and twentieth-century discourse about the âchildâ has mandated that children be innocent but suggested that adults should work to maintain that innocence. But class and race always complicated who was allowed to be a âchildâ in national discourse. Regardless of how much we might want to complicate these constructions, we can still express dismay that young African American children know or must be taught that black boys and men are disproportionately shot by the police in the United States. These child characters are in between adult consciousness and childhood innocence, which is a characteristic of the precocious child in the comic strip. The seriousness of the issue puts a twist on the characteristic child persona in the funny pages.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Kathy Andrews Collection by Kathy Andrews(11797)

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(8956)

Paper Towns by Green John(5167)

Spare by Prince Harry The Duke of Sussex(5167)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(5067)

Industrial Automation from Scratch: A hands-on guide to using sensors, actuators, PLCs, HMIs, and SCADA to automate industrial processes by Olushola Akande(5041)

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(4284)

Be in a Treehouse by Pete Nelson(4025)

Never by Ken Follett(3922)

Harry Potter and the Goblet Of Fire by J.K. Rowling(3835)

Goodbye Paradise(3791)

The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro(3385)

Into Thin Air by Jon Krakauer(3370)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(3358)

The Cellar by Natasha Preston(3319)

The Genius of Japanese Carpentry by Azby Brown(3278)

120 Days of Sodom by Marquis de Sade(3249)

Reminders of Him: A Novel by Colleen Hoover(3065)

Drawing Shortcuts: Developing Quick Drawing Skills Using Today's Technology by Leggitt Jim(3061)